By Stephanie Chase

Guest Columnist

New York, NY, USA

Sarah Davis Buechner performing the Strauss Burleske in D minor

with the Victoria Symphony (Video courtesy of the Victoria Symphony)

Since 2002 it has been my privilege to perform a number of concerts and record with an extraordinary pianist who has also become a dear friend.

In possession of a fearsome technique, Sara Davis Buechner has enjoyed engagements as soloist with many leading U.S. orchestras that include the New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, St. Louis Symphony, San Francisco Symphony, and the National Orchestra in Washington, D.C. Music critics note her "intelligence, integrity and all-encompassing technical prowess" (New York Times) and "thoughtful artistry in the full service of music" (Washington Post), and state that "Buechner has no superior" (InTune Magazine). Her concerts abroad have included appearances with the Japan Philharmonic, the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, the Kuopio Philharmonic of Finland, and the Orquesta Sinfonica de Castilla y Lyon in Spain. She is also a top prizewinner of many illustrious international piano competitions, including the Tchaikovsky and Gina Bachauer Competitions.

Many of these notable accomplishments occurred while Sara was still David Buechner. We had a number of mutual friends through his days as a student at The Juilliard School and played Beethoven's "Kreutzer" Sonata together at a prominent summer festival. In September 1998, one of our friends told me the startling news of his transition, especially so in that David was a "guy's guy" who evidently enjoyed baseball, cigars, and pretty girls. Shortly thereafter, in anticipation of Sara's public concert debut at age 39, the New York Times published a stunningly honest feature that revealed her decades-long struggle with gender identity and the rejections—including, for a period, by her parents as well as many colleagues—that resulted from her transition. Upon reading this, I felt compelled to attend her concert, in which she performed concerti by Chopin. As soon as she started to play I recognized a new, feminine character, and felt enormously moved by its apparent naturalness. Following the concert I went to the green room, sat next to her, and tried to be as supportive as possible. In the years that have unfolded since, it is she who has been tremendously supportive of me; if it were not for Sara, it is likely that I would not be, among other things, teaching at New York University, recording for Koch (now eOne), and advising Dover Publications, and Sara has generously invited me to perform on recitals with her when she could easily play a solo piano concert (and keep the entire concert fee and adulation for herself).

Now living in Canada, Sara remains an inspiring musician and honored friend. Our most recent concert together was in Calgary in January where we performed the three sonatas for violin and piano by Johannes Brahms.

Stephanie Chase

STEPHANIE CHASE: You have made many recordings of a remarkably diverse repertoire, including music by Johann Sebastian Bach, Ferruccio Busoni, Joaquín Turina, George Gershwin, Stephen Foster, Rudolf Friml and Miklós Rózsa, and you play an enormous variety of music in concert. This season alone you are performing as piano soloist with orchestra in music by Mozart, Ravel, Bartok, Rachmaninoff and Grieg. You are an avid proponent of contemporary music, including some exquisite short pieces by Japanese composers, and you even play novelty music, as when you have performed as a special guest with Vince Giordano and the Nighthawks in New York. Were it not for your introduction, I would likely remain unaware of the stunningly virtuosic pianism of Hazel Scott, a beautiful young Trinidadian-American woman whose career flourished in the 1930's and 40's, and who could apparently play anything but specialized in "stride" piano.

In this Conversation we are featuring some recorded selections from your diverse repertoire. Could you please comment on some of the aspects of this music that you enjoy or find meaningful?

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: You mention the scope of my recordings, which is not nearly of the size or variety I'd ideally like, or should I say, what I do intend to leave behind by the time I depart this Earth. Recordings are, for me or I assume any performing musician, the ideal way of leaving an artifact of one's artistic essence. In general I've not strived to record something until I felt I could do so in such a way to make it really worthwhile and (I'll say, humbly) immortal, if such a thing is possible.

I've also felt it unnecessary to record many major works of the piano repertoire that are already much (or over-) recorded. For example, the 32 Beethoven Sonatas—many of which I do love and have played, particularly the Pathétique, the Waldstein, and op. 101. My own teacher Rudolf Firkušný made a wonderful recording of the Pathétique, I love Jacob Lateiner's recording of the Waldstein, and I am stunned by Anton Kuerti's interpretation of op. 101. Moreover the complete Sonata cycle has been recorded many times, my own favorite traversal being that of Badura-Skoda. So what do I need to add to all of that with my own, recorded interpretations—unless I feel they are really superior or more original in some way? There are other works that I love just as much as those Beethoven Sonatas that I do play with strong conviction, and that are sorely in need of being heard.

Having said all of that, I do intend to record in the next couple of years, the complete Mozart piano sonatas (Mozart being the one "standard" composer for whom I feel a pronounced affinity), more music of Friml, another two CDs of Bach arrangements of Busoni and his pupils, a CD of Japanese piano music, and the Beethoven and Brahms Sonatas for Violin and Piano, with the greatest violinist of our time—Stephanie Chase.

STEPHANIE CHASE: I am flattered by this immense compliment—and do hope to have the honor of recording these sonatas with you! Would you speak a bit on the music by composers like Miklós Rózsa, Joaquín Turina, and Rudolf Friml, who are less known to today's audiences and musicians?

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: I'd place Rózsa's 1949 Piano Sonata right at the top of important 20th-century works of that genre, along with the Sonatas of Bartók, Janáček, Szymanowski, and Carter. He was a tremendous composer who is still underrated because he had the temerity to write so many film scores—all of them wonderful and some of them legendary (like Double Indemnity and Ben-Hur). Like Ravel, Hindemith, Mendelssohn, and Mozart, Rózsa wrote with absolute fluency for any instrument. I was astonished after learning Rózsa's Sonata to find out from his daughter Juliet that he was not particularly skilled at the piano (violin was his childhood instrument).

Joaquín Turina is one of the giants of Spanish piano music, along with Falla, Albeníz, and Granados. He wrote 33 picturesque piano suites of stunning and exuberantly passionate sweep. Even the Spanish pianists tend to neglect him, thinking that his piano music is somehow second-tier. They are missing out on one of the greatest colorists of the 20th century. I cannot play Turina without seeing in mind the canvases of Spanish impressionist Joaquín Sorolla—so similar in mood and even content, to the work of Turina. I think of the composer as a painter for the piano, and the painter as a musician on canvas.

Humoresque op. 45 by Rudolf Friml

Rudolf Friml was best known as an operetta composer of the 1910s and 1920s. Very few people know that he studied with Dvořák and made his USA debut as a pianist with the New York Philharmonic playing his own Piano Concerto. He wrote a lot of piano music, much of it salon miniatures and some of it quite complicated but always very, very charming. Fritz Kreisler adored Friml's music and recorded some of his salon encores, and his piano pieces were played by Vladimir de Pachmann and Josef Hofmann, among others. He was a personal friend of my teacher Rudolf Firkušný and wrote some difficult Etudes for him as well, the autographs of which I found in Bard University's archives—fiendish finger-twisters with the adorable title of "Fast and Faster." I'm hoping to play those next season.

The major avenues of piano repertoire are so well-traveled and well-known that pianists themselves forget how interesting the other streets and boulevards can be! There is more repertoire for piano, 500 years of it, than for any other instrument. Yet the appetite for that repertoire seems so restricted. If you could translate it to food terms, you might say that many pianists wish to live in the cosmopolitan center of Manhattan yet only eat the pastrami sandwich at the Carnegie Deli, every morning, afternoon, and evening. It's tasty, fulfilling, and you really won't get tired of it (if you like your fatty meat, salt, and bread). But imagine all the cuisine you'd miss out on if you never went to the restaurants in Chinatown, Little Italy, Greenwich Village, Harlem, or Washington Heights. And I didn't even mention the Bronx – whose Italian restaurants are the best that I know, outside of Italy.

STEPHANIE CHASE: We musicians always relate to food, too—and you and I have shared some great meals together—so I like your analogy. On the subject of your teachers, just last month you postponed a concert to be at the deathbed of Reynaldo Reyes, who taught you starting when you were very young. In recent years you have worked with Paul Badura-Skoda, of whom you speak with great admiration. Who have been your most influential mentors, and why?

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: If I do enjoy an especially diverse appetite, I must give credit where it is due. Reynaldo Reyes was my first major teacher and he was one of the first Filipinos to succeed as a classical musician, studying at the Paris Conservatoire before coming to Baltimore where he settled in the 1960s. Reynaldo taught me from age 5 to 16, raising me pianistically from five-finger exercises and scales, to my audition program for The Juilliard School where I played Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, and the Bartók Etudes. It was a painstaking and dedicated work of art on his part, bringing a small child systematically through so much repertoire, solfège, theory and harmony. There were times that my lessons ran to four hours, and he never charged my poor family a dime. He just expected that I'd pay it forward some day, and indeed I am doing that every time I teach or play the piano.

Sara Davis Buechner

It was in those early lessons that I first heard the rich smorgasbord of language and culture he would speak, when the phone would ring and he'd pick up the receiver. You could never tell in advance what language would emerge from his lips—he was fluent in English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Greek, and Tagalog. He was also forced to learn Japanese as a boy but could not come to speak it as an adult, after the atrocities of World War II that he experienced. Reynaldo Reyes was a true cosmopolitan who appreciated the flavor of every world culture, and he stressed that in his piano teaching. To play Debussy well, Reynaldo impressed upon me the attitude that one must know the taste of the French language in the mouth, know the color of French painting and architecture to the eye, understand the very heart and soul of a French outlook on life. So it was for the Austria of Mozart, the Italy of Busoni, the New York City of George Gershwin. This was the kind of lesson I just soaked up as a youngster, because the Baltimore suburbs of my childhood were so restrictive and sterile. We lived in a small house in a bland all-white neighborhood where big dreams were hard to come by. But every Saturday, I could visit Mr. Reyes and experience the larger world outside that. Through music I came to know Europe, South America, and most tantalizingly of all, Asia. Reynaldo's tales of music-making in the Far East, and his penchant for flying to and from Manila at the drop of a hat, made Japan, China, and the South Pacific seem both exotic and close-at-hand.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Although it must have been nearly unbearable for you, your presence with him in his final hours is testimony to your love and respect for him as well as to the impact that he has had on your life, and he must have found some solace in the legacy that you carry on his behalf. Did your parents play a major role in encouraging your music studies?

Sara Davis Buechner Commemorative Concert

for Ferruccio Busoni in Kyoto, Japan (2016)

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: Within the confines of my own house, I have to thank also my young mother who had larger dreams as well. She and my Dad, who worked for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, barely finished high school. In my youngest memories, Mom fulfilled her expected role as a raiser of children and housekeeper. But she had aspirations for her children, of the typically American kind—we should succeed in a bigger way than our parents, first of all by going to college. To that end she filled our house with good paperback books, the World Book Encyclopedia on subscription purchase, reproductions of masterpieces on the wall (some borrowed from the Pikesville Library), and classical music on the radio. And she bought a battered baby grand piano that sat in our living room. That piano and radio were my deepest loves, from the age of 3.

Into that house came the magical person of Veronika Wolf, about 18 years old, a composition and piano student at the Peabody Conservatory. She had immigrated to America with her parents after escaping from Hungary during the 1956 uprising (running barefoot through the forests outside Budapest with Russian bullets flying above their heads). Somehow my mother came across her name and hired her to come once a week to our house to teach my brother and me, and also to our cousin's house down the street, as well as a few other nearby homes. She was (and is) a brilliant musician, fine composer, extraordinary teacher of children, and I adored her. Later she became a Dean of the Jerusalem Conservatory of Music and Dance. We are still in warm touch a half-century later. Veronika taught me until age 5 when she took me to play for Reynaldo Reyes.

STEPHANIE CHASE: I am always intrigued by how the first connection to a great talent is established, and how often it seems to come almost by chance. That this young woman was able to work with a five-year-old child and ignite that spark is, as you say, magical. And you went on to earn a doctorate at Juilliard, so clearly you excelled at your education, too. As a fellow musician, one of things I admire in particular about you is your desire to learn, improve, and always expand your horizons. What does it mean to you to be a musician?

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: Again, I must thank Reynaldo Reyes for introducing me to the concept of how music and its practice is wholly a byproduct of history and tradition. He spoke often of his own studies in Paris with Jean Doyen, Jacques Février and Marguerite Long. As well, he took me to Washington when I was about 13 years old to play for the great Polish pianist Mieczyslaw Münz, who had been an important pupil of Ferruccio Busoni. I became aware of the rich French and German traditions of pianism that I was inheriting. After I arrived in New York in the fall of 1976, I began to study the music of Busoni (the scores were quite hard to obtain at that time, since Busoni's works were published by Breitkopf in East Germany), and became friendly with Busoni's daughter-in-law Hannah. She was a terribly sweet grandmother-type to me, baked me cookies and cooled my fiery temper on a few occasions, too!

Toccata by Ferruccio Busoni

Playing for some of Busoni's last surviving pupils, Edward Weiss and Gunnar Johansen, and subsequently studying with the great Czech pianist Rudolf Firkušný and American virtuoso Byron Janis, further instilled in me a great appreciation for pianism of the past. At the same time, being fully aware of how the art of music-making does necessarily change and adapt to the present and future. To study, for example, Busoni's brilliant and idiosyncratic pianistic solutions to the complexities of Bach's harpsichord-conceived "Goldberg" Variations, is the gateway to an entirely free appreciation of the possibilities of interpreting Sonatas of Scarlatti, Soler or Seixas; or even how to utilize pedal effects in works of Brahms, Bartók, Hindemith or Berio. The ingenious French fingerings which Reynaldo Reyes shared with me in studying the Ravel Concerto and Debussy Préludes have been of incalculable value when working on keyboard music of Messiaen or Dutilleux, because the sound of that French school is quite interconnected.

I often tell people that the greatest musical thrill of my life was the privilege of studying with Rudolf Firkušný for five years (at Juilliard). He was truly an aristocrat of the piano, and a gentleman of the highest civility and cultivation. My lessons were like visits to an extraordinary shrine. I made it a point to study as much Czech music with him as I could—works of Dvořak, Smetana, Janáček (with whom he had studied composition), Martinů, and Suk (close personal friends), and many others. My interest in his native repertoire brought us very close, and that relationship continues with his daughter to this day. The music itself and its performance traditions were something priceless that he shared with me, and as a teacher and performer now, I feel the obligation of protecting his gift every time I am on stage or giving a lesson.

STEPHANIE CHASE: I had the great fortune to study Janacek's Violin Sonata with Firkušný at the Marlboro Festival. In addition to being a marvelous pianist, he was such an elegant and generous person, and he gave me corrections for the score and taught me about the connection of Janacek's music to his spoken language, which I am trying to pass on whenever possible. Please also tell us about your introduction to Badura-Skoda.

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: Two years ago, I was invited to appear at an important piano festival in Shanghai, China, along with some 15 other pianists from around the world. The elder statesman of that group was the Austrian pianist Paul Badura-Skoda, whose recordings and writings I have long admired. Though he had heard me from the other side of the judges' table at a few international piano competitions, we had never met. He is charming, intelligent, and a deeply probing thinker, and I was drawn to him immediately. On a whim, a few months later, I emailed him and asked if it would be an absurd request to come and play for him. He was quite kind by way of reply and I ended up having my first piano lessons in some 30 years, playing Mozart for him in both Madison, Wisconsin, and then in Vienna at his home. I used the opportunity to learn one of his own piano pieces (he is a very good composer as well as pianist), and gleaned some wonderful tips from him about the Mozart four-hand Sonatas which he has played and recorded so wonderfully with Jörg Demus. I do relish the words of wisdom from elders, and I lament the necessary day which comes when it will be my own turn not to have any around—that is, if I am lucky!

Sara Davis Buechner

STEPHANIE CHASE: As I said earlier, the breadth of your musical interests is truly exceptional, and it's clear that Reynaldo Reyes was a catalyst in introducing you to the music of composers beyond the bastions of the classical genre. What about your interest in the popular styles, such as jazz and salon music? How did this come about?

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: Another blessing I received by way of my mother was an appreciation of music in popular culture—that is, in jazz and on the musical stage, and in motion pictures. She had an innate appreciation of excellence in all mediums. In the evenings after putting my brother and me to bed as very young children, she would play a few piano pieces which always included some easy Chopin Preludes or Waltzes, a few bars of the "Warsaw" Concerto, favorite songs of Jerome Kern, Rodgers and Hammerstein, and the like. My mother's own love of music had not been sponsored much in her own home, but rather at the movies with her older sister Jackie who corrupted her—snuck her into the "film noir" classics of the 1940s which were considered verboten for young girls. My mom also adored Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire, and indeed any good dancing especially if it involved the music of George Gershwin. We had records of Bing Crosby, Ella Fitzgerald, and Erroll Garner next to those of Leonard Pennario, Byron Janis, and Arthur Rubinstein.

In my teens I developed a taste for big band swing music, and astonished my parents at age 14 when I begged them to take me to Washington D.C. for a concert by Benny Goodman, then in his 80s. To their credit, they took me, though I don't think they had half as much fun as I. At the time, Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller were moldy names of their own parents' generation and who wanted to hear that old hat? But I loved it, loved jazz of the 1920s-30s-40s and still do, even though I have no skills for improvisation.

STEPHANIE CHASE: What a great experience! Not many people realize that Goodman was an ardent supporter of classical music and regularly played the "clarinet classics," like the Brahms sonatas, at home. He also premiered Bartok's famous "Contrasts." And I still vividly recall the hearing the jazz violin great Stefan Grappelli play at a small venue near Marlboro, Vermont, when he was in his upper 70s. Did it take a while for you to start incorporating this kind of music into your own program?

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: Only later in my twenties did I begin to program music of George Gershwin and Scott Joplin in my own piano recitals, but once that gate was opened, it liberated me tremendously in terms of programming and repertoire. I won the Gina Bachauer International Piano Competition playing the Gershwin Concerto in 1984, and I believe it may still be the only major classical competition where someone offered that work in the final round. Later I came to know the piano music of Pauline, Alpert, Zez Confrey, Rudolf Friml, and Dana Suesse (thanks to my friend, the great cabaret pianist Peter Mintun). I do not think any of it as "light" music, as it has sometimes been called. To play it well takes command, proper respect, unique study, and cultural understanding. Too often, such music is played poorly out of an innate disrespect and I daresay lack of proper study.

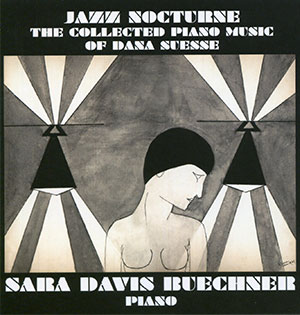

Jazz Nocturne by Dana Suesse

A quote that has stayed with me over the years, from conductor Franz Allers who worked primarily in Broadway pits conducting the Lerner and Loewe musicals, though his training was purely classical: "There is no good or bad music, only good or bad performances." I don't always agree about the first part of that statement, but the second must inform anything a musician chooses to execute on stage. If you play a piece in public, it must communicate as a great piece. That is a crucial part of the performer's job.

STEPHANIE CHASE: That is clearly evident in the variety of your interpretive styles. When we recorded the album of short pieces by Friml together, I spent endless hours working on an appropriate manner of playing these pieces; they are gems but each must convey its own particular, and often quite delicate, character. And I agree with you that there is definitely some bad music out there.

We have spoken about your teachers and their importance. In turn, you have been a professor of piano at institutions that include New York University, Manhattan School of Music, and, since 2003, the University of British Columbia at Vancouver. Has teaching others affected your own technique or musicianship, and what is your best piece of advice for a talented young pianist with aspirations to a concert career?

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: Since my thirties I have been a teacher, and I am now at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. At all of these institutions I have been impressed by the standards of quality and imagination often brought by young people to the piano. As well, I have been impressed by how difficult a profession music is in terms of the passion and the commitment that it truly takes to succeed. Of course, outside the walls of a school lie the depressing reality of the classical music business, but that's a different interview for another time!

I reached one of the starker revelations of pedagogy when I gave a Piano Literature midterm examination at Manhattan School of Music, soon after joining the faculty. It was a large class, about 40 students, and I wanted to find out the extent of their imaginative reach. Instead of giving a paper test, I gave them a few weeks to craft a six-page paper on any topic, something that interested them involving the piano. I explained that they could write about a composer, a performer, something about piano repertory, about the piano and film, or dance, or in brothels, or funeral homes, or whatever. Just gave them total freedom, any subject whatsoever as long as even tangentially it involved the piano.

After collecting the papers, I remember how mathematically the results came out. 10% of the papers, four of them, were truly excellent—imaginative, exploratory, thought-provoking. Essays I really wanted to read, and learn from. Another 20% (8 papers) were perfectly fine, very good—grade A. Another 20% were less good but fulfilled the assignment—grade B. And 50% of the papers were plagiarized, copied straight from books like Donald Francis Tovey's volume on the Beethoven Sonatas.

The dismal economic realities of that conservatory prohibited teachers from tossing out students who indulged in such cheating, which was the biggest scandal of all this—I simply had to elicit another assignment from those pupils. What I retained from that experience was the number—10%. Over the years I have taught, both private piano students and the occasional classroom, I have found that percentage to be rather stable. About one-tenth of the young people who enter classical music truly have the passion, imagination and fortuitous character to stay with it, through thick and thin. As a teacher, I must struggle constantly not to be dismayed by the 90% who either cannot, will not, or truly do not want to take my few seeds of wisdom and try to grow plants from it; but rather to invest carefully in my time with the 10% whose music rewards me over and over and over again, as the years go by.

STEPHANIE CHASE: I think you are right on the mark here. Conservatories and music programs generally do not have the luxury of accepting only the most gifted and motivated students, who may need a substantial scholarship, but sometimes the students surprise us by finding their special—and successful—niche.

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: Yes, I think of the pianist from NYU who became director of the U.S. Marine Corps Band; the cabaret singer/songwriter in Osaka, Japan; the stellar performer in musical pit orchestras now appearing on Broadway; or the pianist/writer/radio commentator in Lisbon who has become a première interpreter of contemporary music. These people were once my own pupils, and with hard work and trust in their own gifts, they are keeping the flames of excellent artistry burning in vastly different but equally extraordinary ways.

Sara Davis Buechner

STEPHANIE CHASE: In rereading the New York Times interview with you from September 1998, I am struck by your candidness and transparency, as if you were feeling liberated from living in disguise despite the many punitive responses that you encountered. It seems that there is now a greater acceptance and understanding of this difficult process—I have friends and colleagues whose daughters have recently transitioned, while still in their teens—but in the late 1990's it seems likely that many transgender persons would have changed jobs and moved to another part of the country, in part to aid in remaking their identity; in fact, the average person changes jobs twelve times in the course of his or her lifetime.

To the contrary, your identification as a concert pianist has remained the constant. I think that in order to be effective interpreters of music, we need to present what we believe is the truth of the music, filtered through our experiences; did your transition from David to Sara cause you to feel differently about how you play the piano and interpret its music?

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: In my mid-thirties I began to confront the puzzle of my own gender identity, which had been suffused with guilt since childhood. One of the greatest barriers to making that necessary journey was my own musical career. Music may be a creative art form, but it does not necessarily translate that musicians or people in the music industry are creatively accepting or encouraging of divergence from the norm. When I came out publicly in 1998—by way of the New York Times Magazine story—it effectively ruined my active career. I found myself looking for a new agent, without concerts, without a teaching job, without family, without a lot of friends who turned out to be no friends at all.

Yamaha Piano, whose instruments I've played since 1986, made a strong statement of support for me, at the time. And I felt lucky to get a teaching job at the Amadeus Conservatory in Westchester, a neighborhood music school for children. At the age of 39, I began a musical career anew at the level of where I had been around age 21.

On many levels, it was the greatest gift of all. Stripped of my identity as David Buechner, I had to relearn a lot of things that needed relearning; because frankly, so much of my personality had become false: the kind of things I wore and said, my cynical outlook, the front I put on especially for male friends whose coded behavior I truly loathed. To be outcast is to be given the special opportunity to redefine all that is important in one's life.

I found a lot of support, surprisingly enough, in the Catholic Church of the Bronx neighborhood where I moved essentially to escape from the Manhattan snake pit where I had experienced a lot of harassment while transitioning. And I enrolled in language classes at the Japan Society, which opened doors to my life I had not even known existed. I resolved to be successful at the teaching job at the Amadeus Conservatory, as hard as it was. Teaching largely untalented little kids is very hard work, requires great patience and compassion—qualities I did not possess much of, at the time. I learned more about teaching at that time than I had ever known before, between returning to student life myself with Japanese assignments and studying how to inspire children who sometimes didn't even want to be learning the piano. Parents sometimes enrolled their children at Amadeus just to have them out of the house for a while.

When I was appointed to the University of British Columbia in 2003—the only University that even bothered to reply to my employment applications, out of some 25 that I sent—I had to cope with moving to a new country, new coast, very new environment. In many ways it was wonderful, as for example my Japanese spouse Kayoko could easily immigrate to Canada and we were married there, which was impossible in the USA at the time. One emotionally hard part of the move came, surprisingly, on the last day I went to teach at Amadeus and told my students that I would not be returning in the fall. One little girl—a freckle-faced tomboy named Katie who had told me defiantly at her first lesson that "I hate the piano!"—asked me where was Vancouver. When I told her it was about 3,000 miles away, on the west coast, she just burst into tears. I hugged her close and asked why she was crying. "Because I love the piano," she replied. Oh, I miss Katie with all her freckles and bruises and poison ivy scratches—probably the best teaching I ever did, to enable that young lady to enjoy music. I hope she still loves the piano.

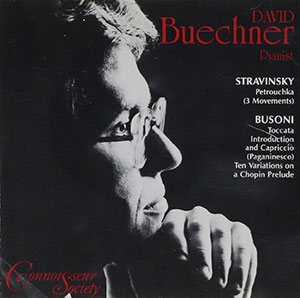

Danse Russe from Petrushka by Igor Stravinsky

STEPHANIE CHASE: I imagine that she does! And I believe that a dedicated music teacher helps students to develop skills that should be useful to them for the rest of their lives, whether they continue in music or not.

In 2016, what are some of the most common misconceptions about transgender people? Is there now, generally, more support and understanding?

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: I've watched with some fascination as awareness of transgender people and transgender issues have become so prominent in the past few years. Of course one reads about celebrities like Laverne Cox and Caitlyn Jenner, but I don't believe their own transition experiences are very typical of the rocky road that most trans-folk travel. In my own travels and after concerts, often I will meet transgender fans or LGBT allies, and at times have given speeches to LGBT groups. It's heartening, and at times very challenging, to hear stories from people who have paid a great price to be integral to themselves in person, to be true to their inner soul.

Rather than feel overwhelmed by the sadness involved in coping with the obvious prejudice and hostility I and other trans-people experience, I try to look on the other side of that mirror and think about the manifold riches I've been privy to that many human beings will never know, and many never ever realize they are missing out on. I recall in my time of gender change, how wrenching it was to sometimes have to wear a suit and tie and present myself formally in some setting as David Buechner—hiding so much of myself, pretending in act and word to be a comfortable male. The clothes I wore then felt like a suit of armour, complete with a mask. After I tossed away that chain mail and mask, I looked freshly on all the people around me and began to wonder, how many of them are still wearing armor and masks themselves? And will they ever discard them? I think, like the percentage of students in that Manhattan School Piano Literature class, maybe 10% of us will reveal what is under our mask.

Because when you stop playing games with yourself and with everyone around you, you can see and hear and smell more clearly, and understand the games that are now swirling around you as non-participant. It's not just about gender, of course—it's about truth and personality and sincerity. How often people are just frightened to ever speak their mind fully because they fear what others will then say or think about them. As Benjamin Disraeli put it so succinctly: "Most people will go to their graves with their music still inside of them."

I think a lot less about identifying myself in terms of male or female, than I do with the thought that I simply didn't want to go to my own grave with my very best music locked up inside. So, I let her out.

STEPHANIE CHASE: If we think about the origins of the word, "music" is derived from the Greek word for "muse." To find that inner inspiration and act on it is to really discover one's self, as you have.

You moved to Canada, in part because you were offered a teaching position there. Unlike the United States, Canada offers a strong national support for the arts and their practitioners, and encourages businesses and individuals to also support the arts. You moved there after having lost many career opportunities at home due to your transition, and have since developed a strong following throughout the country. What would have to happen in the US for this kind of support to evolve here? And do you find that there is a general discrimination against mature women versus older male performers?

Sara Davis Buechner in Rehearsal

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: After moving to Canada, I was able to revive my moribund performing career, mostly north of the American border. I've played with most of the major Canadian orchestras, and on a lot of the prominent recital series. To a small extent this helped with American engagements, though I am still struggling to keep my career afloat down there. Part of this is due to my gender transition, surely; some of it is due to now being female. I find there is just less respect overall for women in the classical music profession than for men. Only two years ago, a major classical music agent told me openly that he thought women should not be conductors. "They don't look right, on the podium." That's the level of thinking that goes on in such offices. Lastly, a whole new generation has come of age since I left the United States, and Youth is big for sales in all branches of commerce. Middle Age is a no-sell. Old is a good sell once you get really old, it seems (just ask the many young fans of Bernie Sanders). So to say, I have confidence that my American concerts will return en masse after I turn 70, God willing.

I miss New York City greatly, though I visit 2 or 3 times a year, sometimes for small concerts there. Manhattan has become a large shopping mall for the bored wealthy, but the Bronx and parts of the other boroughs still retain the ethnic and energy-laden pizzazz that I think of as innately American. Canada is a very earnest country by comparison, and the pizza there stinks. Having said that, Canadians are light years beyond Americans in terms of health care, gender and racial equality, social justice, fair pay, ecological concern, and gun control sanity. This is clear to any American who bothers to make a visit there. It is just beyond me why Americans are content to let other countries trump them (verb intended) in areas they should be leading.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Having just played several concerts in Houston, where many entrance doors carry signs with an admonition against bringing in concealed weapons, I would find Canadian policy a relief on that basis alone, and I hope that it can maintain some of these positive distinctions.

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: Culturally, Canada has complex issues regarding its sense of self-identity, much of that due to their shock at being essentially the 51st State of the USA (that's heresy to say in Canada, by the way). Just what is it that distinguishes Americans from Canadians, apart from poutine and curling? That's more of a serious question that it first appears. When Canadians do distinguish themselves in the arts—e.g. painter Tom Thompson, pianist Glenn Gould, or writer Farley Mowat—their names become common coin, and are known to almost all Canadians, with pride. And that's a wonderful thing. But in too many ways also, Canadians follow their American cousins. One of those ways has been the government de-funding of the arts (particularly during the last, Conservative, government). One of the finest ensembles in the country, the CBC Radio Orchestra, was dismantled only a few years ago. It's a sign of decline in the culture and the country, overall.

Sara Davis Buechner and Stephanie Chase

STEPHANIE CHASE: Although you are now a Canadian citizen, your lovely wife Kayoko is from Japan and you have a special, longstanding fondness for the Japanese and their culture. According to a recent article in the BBC News, however, when it comes to gender equality Japan ranks 104th out of 142 nations. What aspects of Japan appeal to you? Is there a special appreciation for classical music?

SARA DAVIS BUECHNER: The leader of all things concerning punctual trains and spotless toilets—important commodities, in my book—is Japan, where Kayoko and I also have a home now, inherited from Kayoko's mom. I am a committed Japanophile, adoring that country's civility, balanced pace of life (except central Tokyo), food, music, culture, and above all beautiful Buddhist and Shinto temples. Japan is for me, a place of proportion and normality. In Japan, one can enjoy, in equal measure, classical music in concert halls of unsurpassed acoustic perfection; a smooth ride on a gleaming bullet train with ample leg room, gorgeous sushi lunch and superb Japanese beer; a quiet contemplative afternoon in the company of monks at a mountain temple with only the sound of hawks and cranes as accompaniment; the undisturbed attention of perfectly-coiffed sales girls in a department store, regardless of whether you are buying a wedding kimono or the replacement eraser of a mechanical pencil; watching an aged master craftswoman molding silk pens by hand in her tiny onsen (hot spring) studio; the raucous shouts and songs (a different one for each player) of wholly-toasted fans at a baseball game, slurping noodles and potent whiskey with your new best friends in affordable seats with great views of the action on the field and off. This is just a short list of pleasures I recommend there.

To be a gaijin, or foreigner, in Japan is, of course, a different experience than growing up Japanese. And I have many Japanese friends who voice appropriate concern about the country's political direction, its handling of the Fukushima disaster, the growing social issues between older and younger generations. But in Japan I have always found civility, acceptance, cultural sophistication, deep-rooted tradition, and appreciation of history, and I would say above all, grace. Japan is a land of poetry, and as a poet I feel at home there. I think it is a safe prediction that I will live my final days in Japan, preparing for what comes after. And surely the "after" involves music, so I'll keep practicing to be ready for that concert.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Sara, thank you for so generously sharing your inspiring story and remarkable music with me and Stay Thirsty.

Links: