By Eliot Fearey

Seattle, WA, USA

Walking into an exhibition by Seattle-based artist, Casey Curran, is a full on attack of the senses. In his newest series

The Sacred and Profane, the sculptor synthesizes the delicacy of intricate metalwork with the rawness of found animal skeletons and avian plumage. The juxtaposition comes together in a totally unexpected and wonderful way. Beyond the visual aspect, viewers experience the work through an audible element, the squeaking of hinges and clicking of mechanized parts, as well as a tactile component, being able to touch and force the movement of the sculptures. Curran’s work is grounded in the philosophies of 19th century theorists Emile Durkheim and Ernst Haeckel as well as with his childhood observations of the changing landscape around his home in Maple Valley, Washington, due to the confluence of a stream and river outside his backdoor. The work is both visually and theoretically stimulating and Curran has become a hit on the Seattle art scene. Maybe it’s because the work leaves you…tempted to touch.

THIRSTY: Let’s start with The Sacred and Profane, your latest body of work. How did you come up with the idea for those fantastical works?

Curran: I was really interested in Ernst Haeckel’s scientific method and what he was gathering from cultures and around totems. I was especially interested in how a society will separate whatever, maybe a big rock in the middle of a field, and that this object could then become sacred. Before anybody ever came along, the rock was just an object in the middle of a field, left there by the last glacial movement. Suddenly it becomes this sacred thing because people place energy into it. Maybe this is too lofty of an idea, but when people are spending time and interacting with art pieces, they are placing a kind of…not so much of a reverence, but there is a joy that the person initially responds with and I was just interested in that.

THIRSTY: You’ve described the sacred element, can you describe the profane?

Curran: Well, that’s the kicker because the profane is everything that is not sacred. There is a really great Renaissance painting that is called Sacred and Profane and it’s of these two women who are the allegories of what is sacred and what is profane. But, the artist doesn’t say which one is which. One is nude and the other is clothed. They are both just in it and that’s what is so great about the painting for me. It doesn’t really matter which one is which. It spirals down into relativism, which is a horrible, horrible thing to get into because then you are like, “Oh, nothing matters. It’s all fuck, we’re just going to die.” But, it’s fun to skirt it a little bit.

THIRSTY: Some of your works are motorized and others require the audience to participate and initiate the movement of the work. To what extent and in what sense is audience participation interesting to you?

Curran: I’m the most interested in how faces light up when people start playing with it, honestly. But, audience participation is…

THIRSTY: Or, is it not…

Curran: No, it has to happen. I’m making the pieces specifically for the audience. I make something that moves and you have to make it move, or else it’s not done. The audience participation is what finishes the piece, and the audience is perpetually finishing it and making it happen. You know, some of the work is motorized, while others need to be hand-cranked. But, I only like to use motors when the work gets too large.

THIRSTY: Like Walking Spring?

Curran: Yeah, like that one. Putting something as large as that on a crank limits the amount of viewing space somebody has. If you are cranking the piece, then you’re stuck within your arms length of viewing. So, if I want the person to have a view of the whole thing, then I can’t make the piece longer than four feet. My work is not like a lot of other work, like Rothko’s work, for example, where you stand back and can really have the experience with it. My experience is very detail oriented, like you have to get up close and inspect it. I’m asking people to do that. If you look at the wing ventilations on the dragonfly of Unification, everything is made by hand, it’s not cast and they are both symmetric. Making something totally symmetrical is a total pain in the ass, by the way.

THIRSTY: I love the juxtaposition between the delicate metalwork in your sculpture and the very raw and visceral detritus.

Curran: Well, you know I was thinking a lot about organic materials, like looking for horse heads online. I stumbled across these pheasant pelts and I thought, “Wow, these would be amazing to use!” I ordered the first couple from EBay, but they sucked. Then I ordered a couple more and figured out who the better sellers were. Pheasants are such beautiful birds - they look like birds of paradise with all of the different colors in them. They are all about sex.

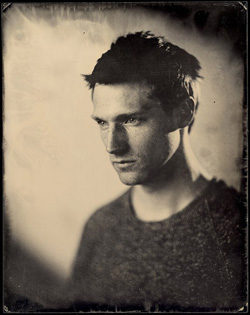

Casey Curran (credit: Daniel Carrillo)

|

THIRSTY: What do you mean?

Curran: I’m just thinking about peacocks and how the guys are…how evolution has pushed the species, and a lot of bird species, into this direction. The color is all about sex and survival and that goes along with birth and death. Well, not birth and death, it’s more about procreation and death. A lot of the time I think about…want to hear a non sequitur?

THIRSTY: Always!

Curran: There is this scientist that took mice, and these numbers are going to be wrong, but let’s just say that a mouse lives five years and that he becomes sexually active at six months. Something really fast! You know, because they are mice. The scientist separated the mice by gender so that they couldn’t procreate until year three and then, remember, they die at year five. He found, in the successive generations, that the mice that waited longer would live longer than the ones that started procreating earlier.

THIRSTY: So, the less sex you have, the longer you live?

Curran: No, not the less sex you have! The later you are when you have sex. You see that with a lot of centenarian. Their parent’s didn’t have children until they were in their 40s or late 30s. You’ll see that over and over.

THIRSTY: What’s next for you?

Curran: I’m going to continue with The Sacred and the Profane because I want to see how the work gets viewed at Woodside/Braseth Gallery, where I am going to start showing my work.

THIRSTY: You mean how the reception to your work changes?

Curran: Yeah, I always wonder about how new audiences will respond to my work.

THIRSTY: Do you think that the audience at Woodside/Braseth might be more conservative than the audience at Gallery IMA?

Curran: I think so. It leads into a whole other thing with the artist issue. Do we make art for ourselves, or are we making art for our audiences?

Leda Breathes the Swan - by Casey Curran

|

THIRSTY: Do you want to elaborate on that?

Curran: I have always definitely made a very concerted effort to try and understand what is popular and what people are driven towards - both visually and conceptually. It’s embarrassing to admit, but after First Thursday, I used to go around to galleries to see what was selling. Just to see what kind of work and which artists were popular. It’s all part of the questions regarding making art for the dealer versus making art for me. I think that they are almost the same person, but not really. I don’t always want to live with my art.

THIRSTY: You don’t want to live with your art?

Curran: No, well, I do. I mean, my art is all around me. But, I don’t always like to have it around me because that means I can’t move on. I would rather disperse it into the universe. The work that I make, I love to look at it and I fall in love with it, but I am really apt to just get rid of it.

THIRSTY: Do you have time for one last question?

Curran: Is it a big one?

THIRSTY: Yes, very. We're in Seattle. How do you take your coffee?

Curran: Black drip.

Curran’s work will be shown in the next “Dorothy K” performance at the Guggenheim Museum on March 13th and 14th. “Dorothy K” is a multi-iteration performance piece organized by the Seattle-based artist collective, Implied Violence. For more information on the performance, please visit The Guggenheim’s Works and Process Festival website.

Link:

Casey Curran

Eliot Fearey is a 19th-century German art scholar, printmaker, and dog walker. She is currently based in Seattle.